The biodiversity of our planet is supported by different ecosystems linked to the terrestrial and marine environments. The marine environment includes a variety of coastal and marine ecosystems that can be classified into major ecosystems. These major ecosystems are coral reefs, the entirety of the deep sea, mangroves, polar ecosystems, salt marshes, seaweeds, Kelp forests, Shallow coastal ecosystem, the pelagic ecosystem (the organisms that live and move within the water column) and Seagrasses.

Seagrasses are flowering plants that have adapted to the life under water. Around 60 different species have been identified in the coastal waters around the globe and just like plants on land, sea grasses depend on light in order to photosynthesize. By photosynthesis they convert carbon dioxide that is dissolved in the water into oxygen and organic matter which makes them part of the carbon cycle.

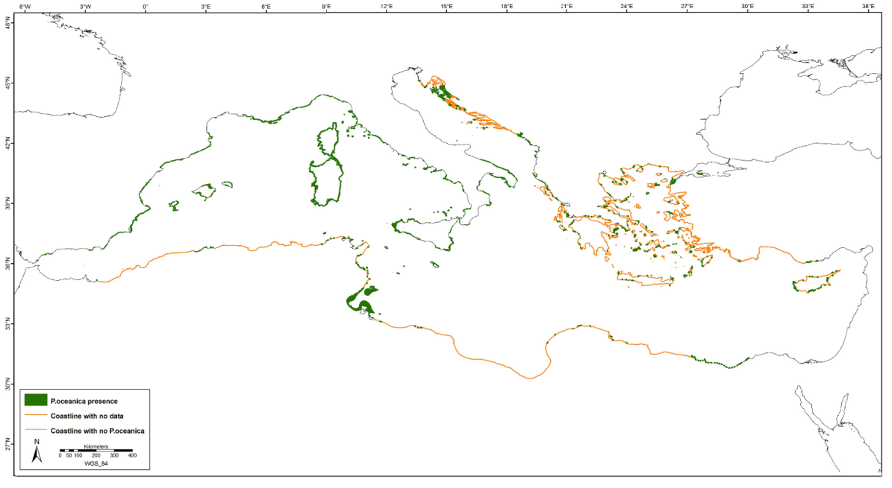

Between all seagrasses the largest amount of carbon is sequestrated (extracted from the environment and stored as organic matter) by the sea-grass species Posidonia oceanica which is endemic to the Mediterranean. There, it covers a known area of 1 224 707 ha [1], growing between depths of several decimeters up to 40 m. In favorable conditions it forms dense root systems called sea-grass matte that can reach thicknesses of several meters.

In addition to carbon storage, the entire structure of a sea-grass meadow and its life cycle provides numerous other important benefits (so-called ecosystem services) to the environment and humans. First, it contributes to coastal protection by preventing erosion. Dead sea grass leaves, that accumulate at the shoreline over time, form so-called banquettes which provide a nutrient input to the beach ecosystem and serve to stabilize beaches at the same time. Furthermore, coastal erosion is prevented by the entire physical (underwater) structure of the sea-grass meadow. On one hand the sea-grass matte root system stabilizes the sediment while and on the other hand the seagrass leaves attenuate waves and swells (make them weaker due to friction). At the same time the leaves facilitate sedimentation and can help to clear waters, which can become important after storms for example.

In addition, the leaves provide shelter for marine species and their offspring from predators and environmental conditions such as currents or storms. The leaves also serve as substrate for epiphytes (organisms that settle and live on top of the leaves such as) which in turn serve as food source for other species.

Map indicating the areas of coastlines with known presence (green), absence (black)

or no available data (orange) of Posidonia Oceanica in the Mediterranean [2].

In many areas however, sea-grass meadows are declining, limiting its positive effects on the environment and its carbon storage capacity. Often the decline can be attributed to several impacts at a time, many of them being of anthropogenic origin. A large proportion of seagrass meadows are impacted by changes in water conditions due to eutrophication and/or direct physical impacts such as coastal work, trawling and anchoring [2].

Once the integrity of a sea-grass meadow is compromised (by anchoring scars for example), the meadow and substrate becomes vulnerable to currents, causing widening of the compromised areas resulting in the recession of the sea-grass meadow. In turn its ecosystem functions are reduced impacting the entirety of the related environment.

Oceanica meadow affected by trawling

On an international level, three conventions recognize the need to protect Posidonia Oceanica seagrass meadows to different degrees (Bern, Barcelona and Ramsar Convention). On a European level, the Habitat, Water framework and Marine Strategy framework directives aim to achieve a good ecological status in all European waters. Subsequently they strive to protect natural habitats such as Posidonia Oceanica which at the same time serves as an indicator for good ecological status. Other policies such as the Common fisheries policy indirectly contribute to the protection of the Posidonia habitat as it prohibits the use of towed gear in areas less than 50m. However, the enforcement of international legislation can be difficult, therefore national legislation is adopted in order to protect the Posidonia habitat. France for example diminishes the negative impact of anchoring on Posidonia for example by the organization of moorings of vessels greater than 45 m.

Apart from the different regulations by legislations, additional damage can be prevented on an individual level by anyone who is aware of the challenges related to the seagrass ecosystem. To avoid additional disturbance, swimmers, snorkelers and divers are advised to move carefully above seagrass areas and to not touch the plants, while paying special attention to the movements of the fins/flippers. More importantly, recreational boaters should avoid anchoring in seagrass beds. To provide a low-impact alternative for boaters, different actors [such as managers of marine protected areas/mooring zone managers] can pro- vide mooring buoys. In order to allow an efficient management of these mooring buoys and to facilitate communication between boaters and mooring zone managers, the BlueMooring platform was developed. It informs the boater about specific regulations in a sensitive area and allows him/her to use the buoys without damage.

REFERENCES

[1] Luca Telesca, Andrea Belluscio, Alessandro Criscoli, Giandomenico Ardizzone, Eugenia T Apostolaki, Simonetta Fraschetti, Michele Gristina, Leyla Knittweis, Corinne S Martin, Gerard Pergent, et al., “Seagrass meadows (Posidonia Oceanica) distribution and trajectories of change,” Scientific reports, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2015.

[2] Nuria Marba, Elena Dıaz-Almela, and Carlos M Duarte, “Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia Oceanica) loss between 1842 and 2009,” Biological Conservation, vol. 176, pp. 183–190.